For the past twenty years, Kassel-based artist Jürgen O. Olbrich has been scavenging paper and cardboard containers looking for printed material—books, manuals, documents, postcards, and reports. Influenced by the Fluxus movement’s rejection of the separation between art and everyday life, his excursions are informed by the goal of losing nothing worth preserving. He is motivated by how everyday culture and history gets lost because the importance of discarded items has been forgotten.

has been scavenging paper and cardboard containers looking for printed material—books, manuals, documents, postcards, and reports. Influenced by the Fluxus movement’s rejection of the separation between art and everyday life, his excursions are informed by the goal of losing nothing worth preserving. He is motivated by how everyday culture and history gets lost because the importance of discarded items has been forgotten.

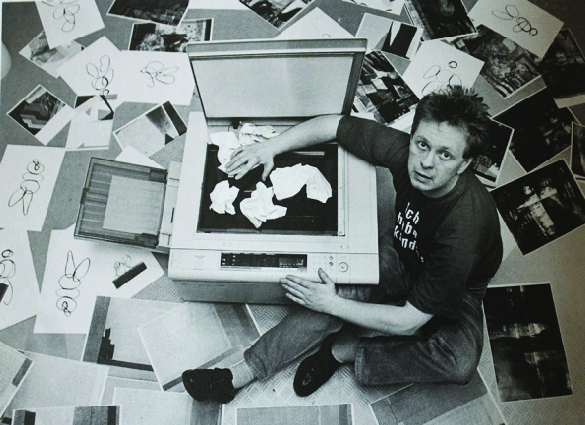

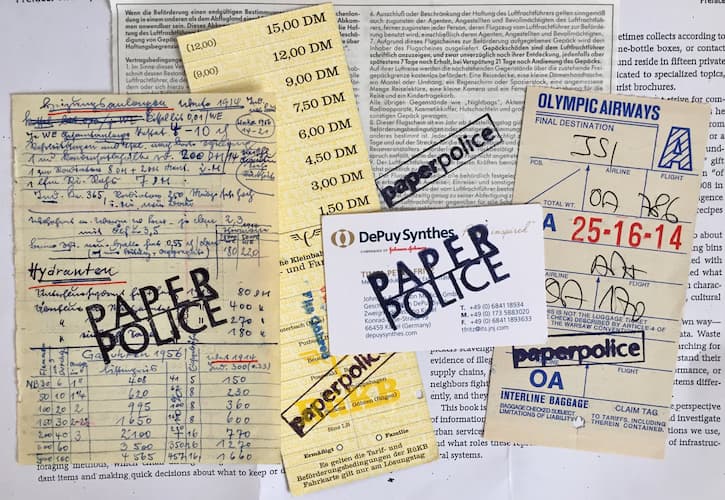

Strictly speaking, Olbrich’s activity might be considered theft. Depending on local ordinances, materials in containers are often regarded as property of the communal recycling company. However, Olbrich has never encountered legal trouble. During his collection trips, he wears a uniform bearing the name Paper Police. By associating the theme of enforcement with his illicit activity, he has, comically and ironically, avoided confrontation. People show him respect during chance encounters at recycling receptacles. Many ask if he has lost something, though he might ask them the same thing.

Olbrich is fascinated by the number of personal documents people discard, oblivious to the possibility that someone else might find them. In the areas around senior housing, he has found documents and keepsakes that chronicle entire lives . In public and busy locations, he frequently finds material that is potentially dangerous or embarrassing for the previous owner, such as bank account information or personal pornography.

. In public and busy locations, he frequently finds material that is potentially dangerous or embarrassing for the previous owner, such as bank account information or personal pornography.

Since starting the project in 1989, Olbrich has diligently refined his methods, hiring employees who receive detailed instructions about his foraging methods, which entail distinguishing between rare and abundant items and making quick decisions about what to keep or discard. He avoids categorizing the items he keeps, but sometimes collects according to themes like paraphernalia about Kassel, perfume-bottle boxes, or contact sheets of photo negatives. Items Olbrich has found reside in fifteen private and public collections, some of which are dedicated to specialized topics, such as a research project on 1930s German tourist brochures.

Olbrich does not see himself as a collector; he does not strive for completeness. He is driven by the anticipation of a lucky find. Sometimes he does find valuable or otherwise noteworthy documents like a letter from Albert Einstein, a 1969 art book from the American artist Ed Ruscha, or a collection of birthday greeting cards from members of the German Bundestag. He often wraps the objects he finds in official “Paper Police” gift wrap , giving the packages to people he encounters to remind them “of what keeps us occupied and what we love.” When I met him in 2008 in Linz, Austria, he gave me a package that bundled a declassified intelligence report about the German Democratic Republic with a collection of recipes involving Jägermeister liquor.

, giving the packages to people he encounters to remind them “of what keeps us occupied and what we love.” When I met him in 2008 in Linz, Austria, he gave me a package that bundled a declassified intelligence report about the German Democratic Republic with a collection of recipes involving Jägermeister liquor.

Through this evolving project, Olbrich has learned a thing or two about his territory. He knows the locations of the most bountiful recycling bins and their weekly collection schedules. He has become acquainted with other foragers who specialize in antiquarian books. He has learned what to look for in certain areas, and associates each neighborhood with characteristic items of waste that he turns into something else: evidence, cultural artifacts, works of art.

There are many like Olbrich who read waste systems in their own way—foragers, gatherers, and trackers of material traces or digital data. Waste pickers scavenging reusable materials, investigative reporters searching for evidence of illegal waste exports, manufacturers trying to understand their supply chains, sanitation departments measuring system performance, or neighbors fighting a proposed transfer station all read waste systems differently, and they all use their specific methods of representation.